We oppose the Town’s plan to build housing on top of the coal ash dump at 828 MLK.

Our town desperately needs housing and, if not for the coal ash, this would be an excellent location. If the coal ash site is not fully remediated, however, we support development using a commercial scenario where the data show acceptable risks of exposure.

Physicians for Social Responsibility published an excellent resource detailing the hazards of coal ash to health.

Here are some of the many reasons that coal ash and housing don’t mix.

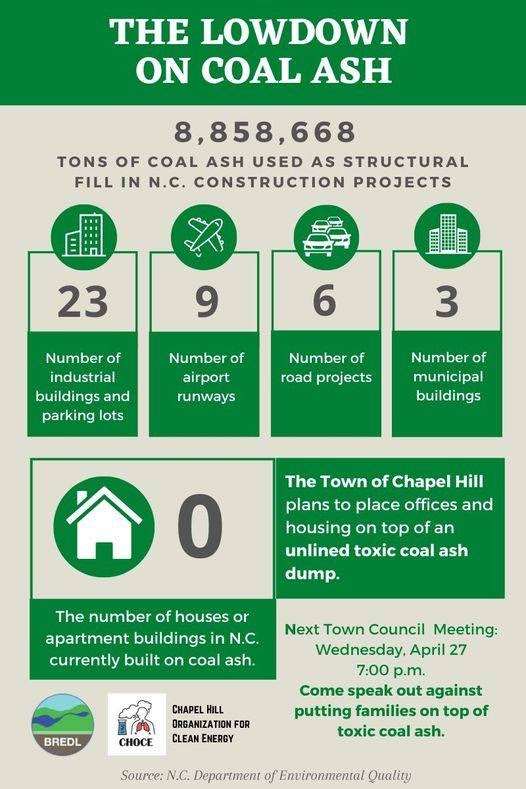

(1) There are no examples we know of where constructing residential housing on top of coal ash has succeeded.

When asked to provide an example of such a project elsewhere in the country, town staff and Belmont Sayre pointed to a housing development in Michigan, Mason Run. However, the developer of that project explains on its website that they did not build the housing units on top of coal ash, and instead removed the coal ash from those areas: “The coal ash wastes posed the most significant environmental challenge. Over 150,000 cubic yards of material had to be removed from the home sites and replaced with an equivalent amount of clean fill.”

What was done at Mason Run is not what is being proposed here; instead, the developer is proposing to build on top of the existing coal ash. The Mason Run development is not an accurate comparison.

(2) Risk of exposure for housing is higher than risk for office workers.

We want to be clear that the health of our town staff is essential. We do and would not support any use of the property that would expose community members to toxic coal ash. So why are we opposing housing specifically?

Housing has stricter health standards because the exposure risk is greater. The town’s consultant assessed health risks of possible future exposures due to commercial, residential, and construction exposure scenarios. Only the commercial worker scenario was within a safe level of exposure. Residents living at the site had 3 times a safe level and construction workers had 10 times a safe level.

Of course, if the site is redeveloped, it will no longer be under current conditions, and construction workers will be required to use safety equipment. But what the town’s risk analysis shows is that the risks are greater for families living on top of the coal ash than they are for commercial or office use. And the risk to construction workers shows that even short-term exposure can be dangerous–that matters for families, especially those with children. Covering up coal ash and contaminated soil with dirt, as the town plans to do, is not a permanent solution for families living on site–there are many examples of coal ash covered with dirt getting exposed over time in residential areas, leading to serious public concern about health risks. Mooresville, NC is a prime example. Coal ash can be inhaled with harmful effects more easily than other sources of pollution, and coal ash that has been covered with dirt can become uncovered through digging, accidents, erosion, etc. over time.

(3) All risk is not eliminated by the capping process.

A landfill, composed of construction debris and coal ash, on a steep slope is inherently unstable. Even with a soil cap and pavement over portions of the site, there will continue to be a future risk of exposure to ash and contaminated soil (for example, due to activities of children or pets, digging, erosion, or structural failure that makes housing not suitable for this site). Coal ash buried adjacent to a steep slope that has been paved over for reuse can fail. As an example, this happened at the We Energies facility in Wisconsin – see before and after photos in this news story.

Concern about the potential environmental and health implications of a full remediation has been discussed. This is a reasonable and understandable concern for community members to have. Senior attorney at Southern Environmental Law Center Frank Holleman, however, calls this an “excavation red herring” used by utilities and other entities to dissuade communities from pushing for a full cleanup. He advises that it’s time to stop “wasting money on legal and consultant fees” to avoid having to excavate coal ash, which “is now the established industry standard.”

Notably, state regulation prohibits owner-occupied housing on this site with cap-in-place. If it’s not good enough for families who own, we should not accept anything less for families who rent.

(4) Children are particularly impacted by coal ash.

“Children have an increased risk of exposure to fly ash. Children have higher rates of respiration relative to adults, increased hand-to-mouth behavior, and a tendency to play near the ground, which increases exposure to ambient particulate matter.”

Research published in Global Pediatric Health: “Health of Children Living Near Coal Ash”

Pollution concerns beyond housing

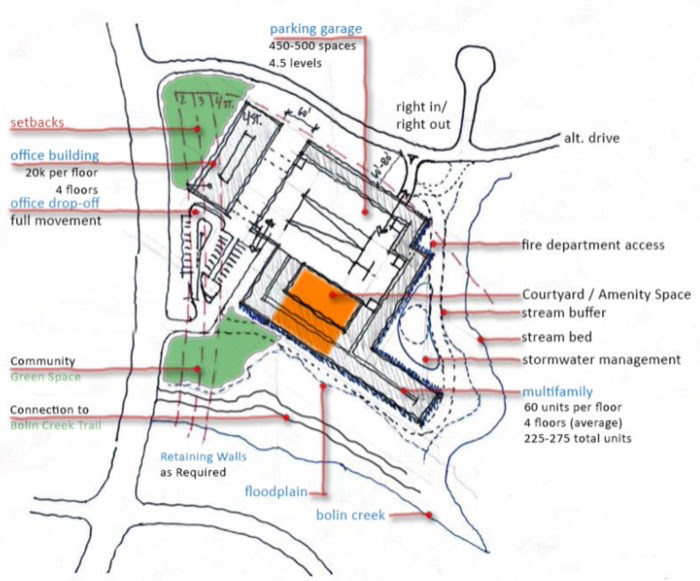

In addition to dropping housing from the plan, these are additional reasons we believe the town should commit to (a) removing the steep slope of ash plus other upland areas of ash using the most protective standards, and (b) monitoring groundwater and Bolin Creek in perpetuity.

(5) The steep bank of ash above Bolin Creek is likely to continue to erode because additional topsoil is easily washed away, as evidenced by the continued daylighting of coal ash on the slope.

The retaining wall will not prevent stormwater from mixing with existing exposed patches of coal ash from being carried down the hill in leachate form to the Bolin Creek Greenway below; nor will it prevent the continued contamination of groundwater by perched water patches trapped in the construction debris and likely to be disturbed when foundations are prepared. See recent pictures of exposed coal ash on the hillside just above Bolin Creek and the Greenway.

(6) Bolin Creek is an impaired waterway on EPA’s 303(d) list.

It also feeds into Jordan Lake, a drinking water supply for up to a million people. Exposed and eroding coal ash on the bank and contaminated groundwater can potentially pollute that drinking water supply.

(7) Flooding catastrophes and intense storms will become only more frequent with climate change.

Witness the on-site video tape of stormwater scouring the coal ash hillside during a storm on the Bolin Creek Greenway. The coal ash and steep slope where a retaining wall would be constructed sit alongside the floodplain of Bolin Creek. More violent and long lasting storms increase the chances of structural problems or coal ash becoming exposed.

(8) Regulations would not allow coal ash as structural fill at this site if permits were sought today…

…and that’s not the only rule that this project would not be able to meet (see below).

2014 NC Coal Ash Management Act (current rules). View DEQ webpage here.

In addition to several other requirements, construction plans must also include:

- A liner,

- Leachate collection system,

- Cap,

- Groundwater monitoring system which is certified by a licensed geologist or professional engineer to be effective in providing early detection of any release of hazardous constituents from any point in a structural fill or leachate impoundment to the uppermost aquifer, so as to be protective of public health, safety, and welfare, the environment and natural resources.

- Sufficient dust control,

- Financial assurance that will ensure that sufficient funds are available for facility closure, post-closure maintenance and monitoring any corrective action required, and to satisfy any potential liability for accidental occurrences, and subsequent costs in response to an incident, and

A structural fill must not be:

- Within the 100-year floodplain; it shall not restrict the flow of the 100-year flood, reduce the temporary water storage capacity or result of washout of the waste to pose a hazard to human life, wildlife or land or water resources.

- Within four feet of the seasonal high ground water table.

- Within 25-feet of a property boundary, bedrock outcrop.

- Within 50-feet of a property boundary, wetland, bank of a perennial stream or other surface water body.

- Within 300-feet of a private dwelling or well.