And after they had consulted together, they bought with them the potter’s field, to be a burying place for strangers. For this…was…the field of blood, even to this day. –Matthew 27: 7-8

By Ann J. Loftin

Take a walk through Northside on a warm spring day. You’ll see houses dating back to nearly every architectural period in American history. Unlike most neighborhoods in Chapel Hill, which began as subdivisions, this place grew organically, built for and by African-Americans who labored for UNC. The land was likely given to freed slaves after the Civil War. Some old-timers still call this area Potter’s Field, a term in the Bible for land valuable only for making clay pottery, or used to bury the poor. For more than a century, African-Americans thrived here. They owned and operated most of the businesses north of the university and west of Church Street – laundries, grocery stores, hairdressers, shoe stores, gas stations, movie theaters, funeral homes, and bars and restaurants. They served the university as builders, stonemasons, janitors, porters, waiters, nurses, cooks, gardeners and clerks.

Segregation made the neighborhood strong: Common employer, common enemy, and sometimes, true alliances forged across the divide. Few opportunities, but consolations. You didn’t come home from church one Sunday afternoon to find some white man walking across your backyard, jotting notes, a speculative gleam in his eye. You didn’t hear Metallica blasting from the second-story window of a new student rental in Pine Knolls. On a janitor’s salary at UNC, with his wife cleaning house for white families, a man could buy, or build, a modest one-story home and raise a family. Walking to work, that urbanist beau idéal, wasn’t optional. Few working-class blacks owned cars, and there were no buses, either, let alone Tar Heel-blue buses full of students wearing carefully ripped jeans. So you lived walking distance to UNC, and your kids walked the 1.5 miles to Lincoln High School, and in 1969 you voted for Chapel Hill’s first black mayor, Howard Lee, who delivered the town’s first bus service, and who replaced the foul-smelling ditch on Mitchell Lane with town sewers. Never mind that Mayor Lee and his wife chose to integrate that new subdivision on the eastern edge of town, Colony Woods. They were moving up in the world.

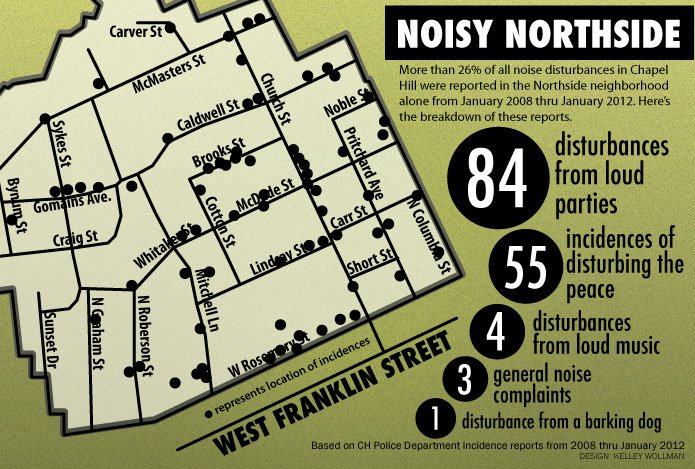

These days, it’s mostly students moving to Northside. Hummers and Range Rovers dig muddy trenches in the lawns of nominally refurbished and subdivided houses, where UNC undergraduates rent by the room. A few elderly African-American homeowners still sit on the front porch, calling out friendly greetings. But they don’t like the new cars, or the new music, or the constantly changing menu of youngsters who come and go at all hours, piling up mounds of pizza boxes and trash on the curb.

“I don’t know what to say about Northside,” said Vivian Foushee, a social worker who attended the all-black Orange County Training School back in the day. She still lives in her childhood Northside home. “I don’t know what to do, and I don’t like what I feel. Someone said to me last night, ‘Did you hear they’re going to put a 10-story building over Breadmen’s?’ ”

We discuss the developers’ application to rezone this 2.2-acre site on Rosemary Street and build a massive complex of rental apartments. “This project will help return Northside to more affordable, well-maintained, family-oriented dwellings,” the developers’ application states. Town Council members and Chamber of Commerce leaders speak from the same script when defending downtown redevelopment. It’s all nonsense, of course; the new buildings simply draw more students to Northside. Yet if approved, Amity Station will join Shortbread Lofts and Greenbridge and all the other high-rise buildings on Rosemary Street, towering over Northside like some wrathful god.

“You know what it feels like to me?” said Foushee, at the end of a meditative and sometimes anguished conversation about the past and present of her neighborhood. “It feels like a rape that nobody has noticed.”

That Northside survived largely intact through the 1980s is testament to its homeowners’ determination. The first assault took place in the 1960s, when land surveyors targeted the neighborhood for “urban renewal,” or “negro removal” as the government program quickly became known. Residents were offered money to move and build elsewhere, but chose to stay and fight. Subsequent decades brought fresh challenges for survival.

Starting in the 1990s, Northside became an irresistible target for real estate speculators. People like Mark Patmore, from Leicester, England, saw a neighborhood ripe for the taking. Patmore came to Chapel Hill in 1995, with vague ideas of taking courses. He bought a house on Brooks Street, converted it into a duplex, and rented half to students to pay his living expenses for the other half. He quickly saw a new career path. He says he sent “blanket marketing letters” to all his neighbors that read, “Why waste your money paying a broker? Give me a call if you want to sell your house.” Patmore’s company, Mercia Properties LLC, now owns 45 rental units in Northside, all rented to students. “Sometimes I have great kids, sometimes they’re a nightmare,” he said. “But I knew this was a student town, I knew I’d have students for neighbors. Anywhere near UNC there will be students. Loryn Clark [a planning director for the town] says she wants to make this a family neighborhood. Who are these families? They’re not calling me.” Asked whether he would favor a more owner-occupied neighborhood, Patmore said, “I don’t want to sell my houses. Why would I do that? It’s farfetched to think I’d do that out of the kindness of my heart. It’s not my job to be a socialist.”

In the mid-1970s, Estelle Mabry, a graduate of UNC’s first coed class, bought a small house just over the invisible line that divided whites from blacks. The color line soon vanished in the face of the real enemy, gentrification, and Mabry spent decades fighting alongside her Northside neighbors. “We went to the town council after all the letters [from Mark Patmore] started coming, and we asked for help,” she said. “We wanted the town to create a revolving fund so we could buy the houses ourselves.” Empowerment, a nonprofit that provides affordable rental housing in Northside, came out of that failed effort, the first of many, to enlist town council support.

Residents also urged the town council to put the next elementary school in Northside, again with no success. Roger Perry’s Meadowmont development off N.C. 54 got the new school, and the Northside kids got bused over there. Finally, in 2014, a gleaming new energy-efficient elementary school appeared on Caldwell Street in Northside, with solar tubes, a roof garden, a rainwater cistern, and a $12.8 million price tag. Since few children now live in Northside, most are bused in from Parkside and other subdivisons in north Chapel Hill.

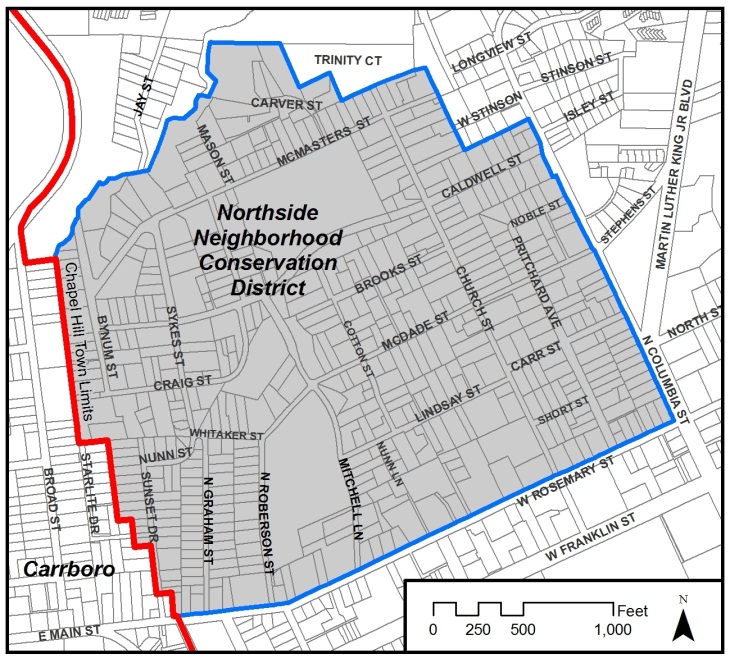

In 2004, having stood by for more than a decade while investors transformed huge chunks of Northside into housing for undergraduates, the town council helped to create Chapel Hill’s first Neighborhood Conservation District (NCD). The NCD imposed height and total-square-footage restrictions, and set a limit of four – residents argued for two – unrelated people who could live in a house. Unfortunately, as a 2011 study from the recently dismantled UNC Center on Poverty, Work and Opportunity pointed out, the NCD proved “toothless,” as “developers of student rentals easily found ways to circumvent NCD restrictions,” and investors lobbied furiously against it. Mark Patmore even sued the town. He lost, in April 2014, but in a larger sense he won. Town staff and council now show little appetite for time-consuming and costly litigation.

The town has several times attempted to enlist support from Northside residents for downtown redevelopment. In 2010, Dwight Bassett, Chapel Hill’s economic development officer, unveiled his “Downtown Framework and Action Plan” to a large group at St. Paul’s AME Church on Rosemary Street. The consultant on the project, brought in from Raleigh to give a presentation, reportedly called Northside an “underperforming asset.” Residents were outraged. “Downtown Imagined” and “Rosemary Imagined,” the town’s most recent efforts to rebrand area redevelopment, fared no better.

But it was Greenbridge that really broke Northside’s heart. A $60 million, 10-story showboat, intended to transform downtown Chapel Hill into a hip, energy-efficient, high-density district, Greenbridge went up on Rosemary Street despite a recession and universal protest by local residents. Developer Tim Toben made some design concessions under fire – an expense the developer would later blame for bankrupting the project – yet still the tower went up, forever changing the neighborhood’s character. Dave Mason Jr. grew up on the block Greenbridge replaced, working first at his uncle’s store, Mason Grocery, and later at the Mason Motel and Starlight Supper Club, where James Brown and Ella Fitzgerald stayed and performed. The plaza in front of Greenbridge is named for Mason’s uncle. “When I see that new building, I see it and I don’t see it,” said Dave Mason. “I see the memories – the Starlight club, and things of that nature. Greenbridge doesn’t fit the neighborhood.”

The Marion Cheek Jackson Center, another relative newcomer to Northside, tries to fit the neighborhood. Della Pollock, a UNC professor of communications, runs the nonprofit along with her former student and protégé, Hudson Vaughan. Named for the historian of St. Joseph Christian Methodist Church on West Rosemary Street, the center operates from a small house next door to the church. What began as a vessel for Pollock’s interest in oral history has grown into a full-time staging ground for community activism. Pollock recalls what Northside resident Ed Caldwell told her in 2001, when she began collecting stories about Lincoln High, the African-American school on Merritt Mill Road: “Y’all have studied the hell out of the black community and given nothing back.”

The Jackson Center aims to give back. It publishes a monthly newsletter for Northside residents; supports a food pantry of fresh produce, meats and dairy products; records and preserves oral histories; teaches students how to be better neighbors; and produces a youth radio broadcast. The Jackson Center was instrumental in getting a six-month moratorium on development in 2011, and it helped create the Northside and Pine Knolls Community Plan, adopted by the town council in 2012, to mitigate conflict between students and longtime residents.

In mid-March the Jackson Center and UNC called a press conference at the Hargraves Community Center to announce an ambitious new program in Northside. UNC Chancellor Carol Folt pledged a $3 million, 10-year, zero-interest loan to buy properties that might otherwise fall to investors. A Durham nonprofit, Self Help, has been enlisted to buy up key parcels and bank them until the Jackson Center, or another nonprofit, can find deserving buyers. The town of Chapel Hill agreed to pay $186,000 toward as-yet-unspecified operating expenses, for the first year. “This is a historic day for the Northside neighborhood,” said Mayor Kleinschmidt. This loan will “empower the community to define its own future,” he said.

Privately, a few longtime Northside residents expressed skepticism about what looked to them like another land grab by UNC. They recalled how, in the mid-1980s, the university tried to cut new streets through the neighborhood, potentially razing Walker’s Funeral Home and destroying many residents’ homes. Then, only a community-wide uproar, coupled with a shortfall in state funds, halted the project. Now it appeared that the university’s real estate developers were looking to buy their way in.

Della Pollock says she hopes “all of our partners,” by which she means affordable housing nonprofits Habitat, Empowerment, CASA and Community Home Trust, “will thrive because of these shared resources.” Pollock envisions matching upgraded houses with UNC employees eager to embrace “the trend toward living small.” As she says, “More than 60 percent of UNC’s staff lives more than 10 miles away, and 30 percent live more than 30 miles away, so it’s very difficult to retain and build a Carolina community.”

What will the Carolina community of the future look like? Past and present demographics may yield some clues. Chapel Hill was one-third African American in 1940. Today blacks make up less than one-tenth of the population, while Asian Americans are 12 percent and 9 percent are mixed race. Maybe Northside will become an Asian-American community, or maybe in the future people won’t tend to cluster along racial or ethnic lines. Chapel Hill’s new breed of developer and politician appears to care only about one color, the color of money. Maybe Northside will just be very, very green.

Only a handful of people showed up at the Jackson Center the other day for a “listening session” convened by Chapel Hill Town Manager Roger Stancil. Among those present were Hudson Vaughan and Della Pollock from the Jackson Center; AME church pastor Thomas Nixon; Knotts funeral home director Michael Parker; and Dolores Bailey, executive director of Empowerment. Town manager Stancil told the group he wanted to hear what the town is doing well, and what it could do better. Delores Bailey took the bait. “You’re approving all these new buildings, but where is the diversity? There are no economic opportunities for lower-income African Americans, and it feels intentional. People feel like, ‘They don’t want us here, they’re waiting for us all to leave.’”

Funeral parlor owner Michael Parker asked why small business owners weren’t consulted about new businesses on their street. “Why do we have a beer joint across from a funeral home?” asked one participant. “How comfortable is that, when people walk out after seeing a body?” Rev. Nixon described being told, in the middle of church funeral services, that mourners would have to move their cars or be towed. “This part of town is so vulnerable,” said Delores Bailey. It was a gloomy meeting, made more so by Roger Stancil’s summary statement. “This is a very critical time,” he said. “The development pressure is intense, and it’s only going to increase because of Northside’s proximity to the university.”

Jackson Center director Della Pollock believes that UNC’s $3 million loan can help stabilize the neighborhood, and she may be right. But if the university really wanted to help residents of Northside it could start by requiring undergraduates to live on campus, where at last count 600 beds lay unoccupied. The $3 million might be better spent upgrading dormitories with the kinds of amenities developers are using to lure students to Northside.

This loan will not repay UNC’s immense debt to the African-American families who cared for the grounds and buildings and students of North Carolina’s flagship university. Some descendants of those families are still living in Northside. Their roofs need fixing, their air-conditioning systems need replacing, and they’d really like some peace and quiet.

Surely that’s not too much to ask.